By: Mahin Gonela

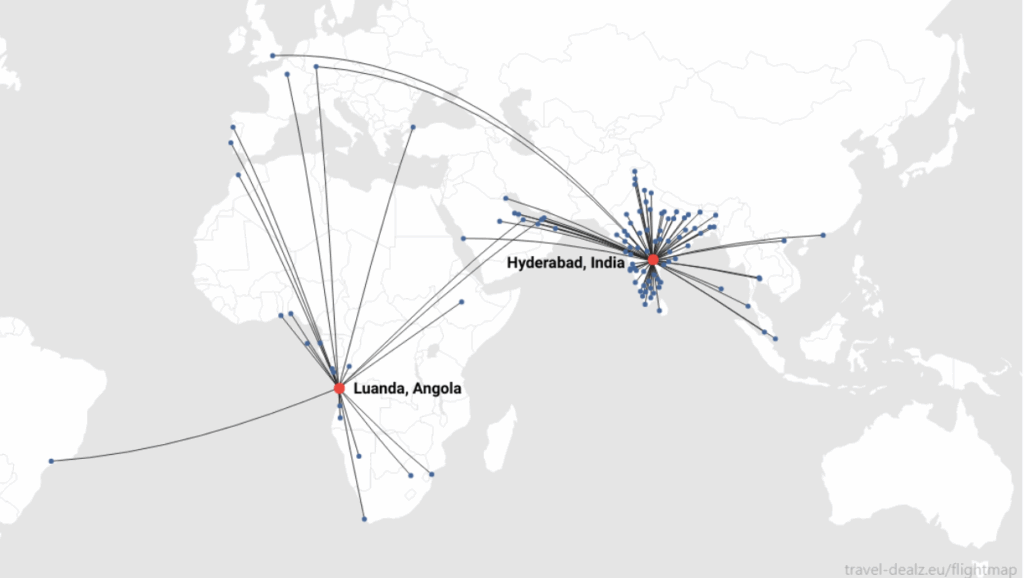

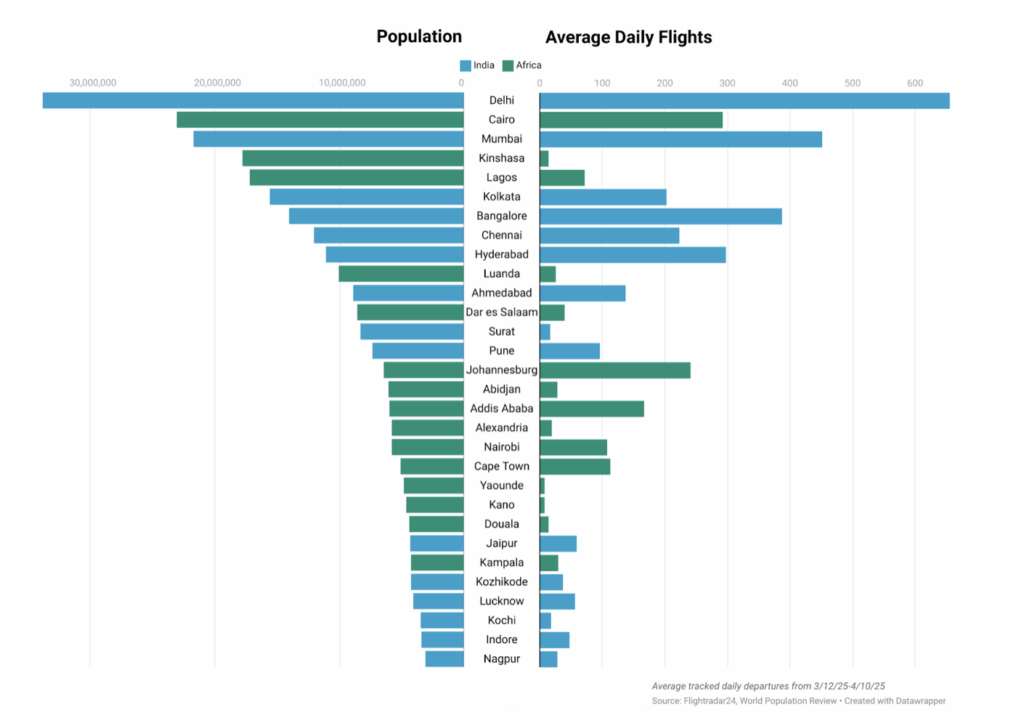

Luanda, the largest city in Angola, is home to over 10 million people. In addition to being the capital, it is the economic and industrial center of Angola, serving as the primary gateway for international business in the country. Despite this, there are on average only 27 flights departing from the city a day. In contrast, the city of Hyderabad, India, which has a comparable population of 11 million, hosts almost 300 departing flights daily. This pattern is reflected across the African continent, wherein large cities have significantly fewer daily flights than their similarly sized Indian counterparts. Kinshasa has 15 compared to Kolkata’s 204, Lagos has 72 while Bangalore has 388, and Dar es Salaam has only 40 whereas Ahmedabad has 137.

Flights are the primary means of international travel across long distances. People travel for business, leisure, and to visit friends and family. They represent tangible links connecting cities and countries. Thus, the lack of flights to a particular city suggests a disconnect from the global economy. Like India, the economies of most African countries are still developing. Yet, the difference in flight traffic between the two raises the question: why are African cities so much more disconnected from the global economy than Indian cities?

In order to answer this, it is important to examine how these cities have grown over the past few decades. In the case of Luanda and Hyderabad, both cities have added millions of new residents since the 1990’s, but this growth has been fueled by different factors. The growth of Hyderabad has been driven by job creation across a diverse array of sectors such as the IT, pharmaceutical, and manufacturing industries. Major international companies such as Microsoft, Amazon, and Google have set up offices in the city, bolstering its status as an international economic hub. On the other hand, urbanization in Luanda was primarily driven by the fact that there were few other places in the country for people to move to. During and after the Angolan Civil War, Luanda remained as one of the only safe locations in the country where people could seek out economic opportunities. Meanwhile, the economic opportunities within the city are largely limited to the oil industry, which is not sufficient to create a diversified economy and generate enough jobs to support a city as large as Luanda. People moved to Luanda not because they wanted to, but because they had to, while the few jobs that created actual wealth remained inaccessible to the majority of the population, creating a city with vast inequalities. This has left Luanda disconnected from the global economy.

The situation of Luanda is reflective of a larger trend occurring within various countries across Africa, where countries are urbanizing without globalizing. The economies of many African countries are dominated by the extraction and export of natural resources such as oil, timber, and minerals. The vast majority of Nigeria’s exports are petroleum products; Tanzania’s largest single export is gold; copper and cobalt make up the largest exports for the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Resource extraction-based industries generate demand for certain urban goods and services, but the jobs created as a result of this demand are often low-paying service jobs in the informal sector. As a result, wealth in these cities remains concentrated in the hands of the socioeconomic elite, which creates little incentive to build and maintain public services and infrastructure. Only one city in all of Sub-Saharan Africa (Lagos) has a metro system, whereas 17 cities in India have metros. Greater investment in public infrastructure helps lower the cost of doing business in a city, which incentivizes companies to invest and create jobs. Poor infrastructure in cities also disincentivizes tourism, which is another large industry that creates jobs and increases the demand for flights. Out of the top 15 largest cities in Africa, the only two with more than 200 daily flights are Cairo, Egypt, and Johannesburg, South Africa. Egypt and South Africa are the second and fourth most visited countries in Africa respectively, which helps to explain the higher number of flights for cities in those countries. Cape Town, a major international tourist destination in South Africa, has 113 daily flights, whereas Yaounde, Cameroon, has only 8, even though both cities have around 5 million people.

Historically, urbanization has been a sign of economic development since the Industrial Revolution. Cities like London and Paris grew rapidly in the 19th century, New York and Tokyo in the 20th century, and Guangzhou and Shenzhen in the 21st. In these instances, urban growth was largely driven by manufacturing and service sectors creating enough new jobs to entice people to move from rural areas to cities. This traditional pattern of urbanization is the one that most Indian cities are following. Mumbai’s growth has been fueled by the financial and entertainment industries; Hyderabad and Bangalore by the tech industry; and Chennai by the automotive and healthcare sectors. Cities like Luanda, Kinshasa, and Lagos on the other hand, have urbanized due to factors like conflict, climate change, and the lack of rural job opportunities, pushing people to move to the only areas with wealth in those countries. Yet, this wealth remains inaccessible to most people who move, creating a society with severe economic inequality.

The differences between the wave of urbanization taking place in India versus Africa highlights the failure of many African governments to build cities that serve the people who live there. Instead, many African cities have been built with the rich elite in mind, with projects such as grand stadiums, statues, and high-rise apartments being prioritized over public transit, power, and sewage infrastructure. If these countries seek to transition from being developing nations to becoming industrialized, globalized states, then they must redefine their development priorities by starting at the city level.